Next: Diophantine geometry

Up: Diophantine Equations and Diophantine

Previous: Linear recurrence sequences

We start with some history. Let  be a real irrational algebraic

number

of degree

be a real irrational algebraic

number

of degree  and let

and let  .

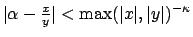

In 1909, Thue [28] proved that

for any

.

In 1909, Thue [28] proved that

for any

, the inequality

, the inequality

(6)

(6)

has only finitely many solutions in pairs of integers  with

with

.

After improvements of Thue's result by Siegel, Gel'fond and Dyson,

in 1955 Roth [22] proved that

(6) has only finitely many solutions

in pairs of integers

.

After improvements of Thue's result by Siegel, Gel'fond and Dyson,

in 1955 Roth [22] proved that

(6) has only finitely many solutions

in pairs of integers  with

with  already when

already when  .

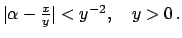

This lower bound

.

This lower bound  is best possible, since by a result of Dirichlet

from 1842,

for any irrational

real number

is best possible, since by a result of Dirichlet

from 1842,

for any irrational

real number  there are infinitely many pairs of integers

there are infinitely many pairs of integers  with

with

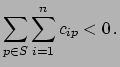

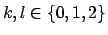

In a sequence of papers from 1965-1972, W.M. Schmidt proved a far

reaching higher

dimensional generalization of Roth's theorem, now known as the Subspace

Theorem.

For a full proof of the Subspace Theorem as well as of the other results

mentioned

above we refer to Schmidt's lecture notes [25]. Below we

have stated

the version of the Subspace Theorem which is most convenient for us.

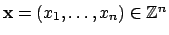

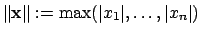

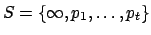

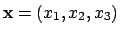

We define the norm of

by

by

.

.

Subspace Theorem (Schmidt).

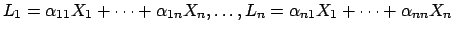

Let

be  linearly independent linear forms with real or complex algebraic

coefficients

linearly independent linear forms with real or complex algebraic

coefficients

. Let

. Let

be reals with

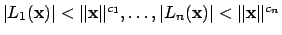

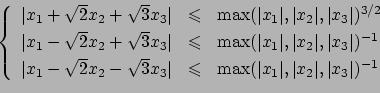

Consider the system of inequalities

be reals with

Consider the system of inequalities

(7)

(7)

to be solved simultaneously in integer vectors

.

.

Then there are proper linear subspaces

of

of

such

that the

set of solutions of (7) is contained in

such

that the

set of solutions of (7) is contained in

.

.

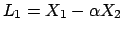

Roth's Theorem follows by taking  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  . Thus, if

. Thus, if

is a solution of

(6)

with

is a solution of

(6)

with  then

then  also satisfies (7).

also satisfies (7).

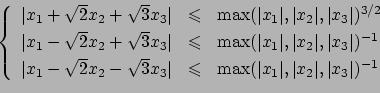

We give another example to illustrate the Subspace Theorem.

Consider the system

(8)

(8)

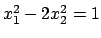

The Pell equation

has infinitely many solutions in

positive

integers

has infinitely many solutions in

positive

integers  . It is easy to see that if

. It is easy to see that if  is a solution

of the

Pell equation with

is a solution

of the

Pell equation with

and if

and if  , then

, then

is a

solution of (8). Thus, the subspace

is a

solution of (8). Thus, the subspace  contains

infinitely many

solutions of (8).

One can prove something more precise than predicted by the Subspace

Theorem,

that is, that (8) has only finitely many solutions with

contains

infinitely many

solutions of (8).

One can prove something more precise than predicted by the Subspace

Theorem,

that is, that (8) has only finitely many solutions with

.

.

In 1977, Schlickewei [23] proved a so-called p-adic version

of the Subspace Theorem, involving, apart from the usual absolute value,

a finite

number of p-adic absolute values. Given a rational number

and a prime number

and a prime number  , we define

, we define

where

where  is

the exponent

such that

is

the exponent

such that

with

with  integers not divisible by

integers not divisible by

.

For instance,

.

For instance,  and

and

. The

. The  -adic absolute value

-adic absolute value

defines a metric on

defines a metric on

. By taking the metric completion

we obtain a field

. By taking the metric completion

we obtain a field

. Let

. Let

denote the algebraic closure of

denote the algebraic closure of

.

The

.

The  -adic absolute value can be extended

uniquely to

-adic absolute value can be extended

uniquely to

. To get a uniform notation, we write

. To get a uniform notation, we write

for the usual absolute value

for the usual absolute value  , and

, and

for

for

.

We

call

.

We

call  the infinite prime of

the infinite prime of

. We will use the index

. We will use the index  to

indicate

either

to

indicate

either  or a prime number.

Then we get:

or a prime number.

Then we get:

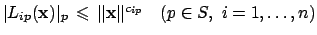

p-adic Subspace Theorem (Schlickewei).

Let

consist of the infinite prime

and a

finite number of primes numbers. For

consist of the infinite prime

and a

finite number of primes numbers. For  , let

, let

be linearly independent linear forms with coefficients

which are

algebraic over

which are

algebraic over

. Further, let

. Further, let  (

(

,

,  )

be reals

satisfying

Consider the system of inequalities

)

be reals

satisfying

Consider the system of inequalities

(9)

(9)

to be solved simultaneously in

.

.

Then there are proper linear subspaces

of

of

such

that the

set of solutions of (9) is contained in

such

that the

set of solutions of (9) is contained in

.

.

There is a further generalization of this result, which we shall not

state,

dealing with systems of

inequalities to be solved in vectors consisting of integers from a given

algebraic number field. This generalization has a wide range of

applications,

such as finiteness results for Diophantine equations

of the type considered in the previous sections,

finiteness results for all sorts of Diophantine inequalities,

transcendence results, finiteness results for integral points on

surfaces, etc.

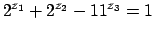

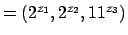

As an illustration, we consider the equation

(10)

(10)

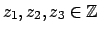

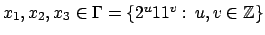

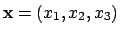

to be solved in

.

It is easy to see that

(10) has only solutions with non-negative

.

It is easy to see that

(10) has only solutions with non-negative

.

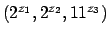

Notice that

.

Notice that

is a solution of

is a solution of

in

in

.

Hence equation (10) may be viewed as a special case of (2).

.

Hence equation (10) may be viewed as a special case of (2).

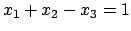

Put

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

.

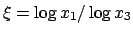

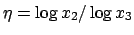

Then

.

Then

and

and

.

Hence there are

.

Hence there are

such that

such that

and

and

. We consider those solutions

with fixed values of

. We consider those solutions

with fixed values of  . Notice that these solutions satisfy the

inequalities

. Notice that these solutions satisfy the

inequalities

This system is a special case of (9),

and since the sum of the

exponents is  we can apply the p-adic Subspace Theorem with

we can apply the p-adic Subspace Theorem with

.

.

Taking into consideration the possibilities for  , we see that

, we see that

is contained in the

union

of finitely many proper linear subspaces of

is contained in the

union

of finitely many proper linear subspaces of

. Considering the

solutions

in a single subspace, we can eliminate one of the variables

. Considering the

solutions

in a single subspace, we can eliminate one of the variables

and obtain an equation of the same type as (10), but in only

two variables. Applying again the p-adic Subspace Theorem but now with

and obtain an equation of the same type as (10), but in only

two variables. Applying again the p-adic Subspace Theorem but now with

,

we obtain that the solutions lie in finitely many one-dimensional

subspaces, etc.

Eventually we obtain that (10) has only finitely many

solutions.

,

we obtain that the solutions lie in finitely many one-dimensional

subspaces, etc.

Eventually we obtain that (10) has only finitely many

solutions.

In 1989, Schmidt [26] obtained a quantitative version of his

Subspace

Theorem, giving an explicit upper bound for the number of subspaces  .

Since then, his result has been refined and improved in several

directions.

In particular Schlickewei obtained quantitative versions of his p-adic

Subspace

Theorem which enabled him to prove weaker versions of Theorem 1 with an

upper bound depending on

.

Since then, his result has been refined and improved in several

directions.

In particular Schlickewei obtained quantitative versions of his p-adic

Subspace

Theorem which enabled him to prove weaker versions of Theorem 1 with an

upper bound depending on  and other parameters and of

Schmidt's theorem on linear recurrences with an upper bound depending on

and other parameters and of

Schmidt's theorem on linear recurrences with an upper bound depending on

and other parameters.

Finally, Schlickewei and the author [7] managed to prove

a quantitative version of the p-adic

Subspace Theorem with unknowns taken from the ring of integers of a

number field

which was strong enough to imply the upper bounds mentioned in the

previous sections. We will not give the rather

complicated statement of this result.

and other parameters.

Finally, Schlickewei and the author [7] managed to prove

a quantitative version of the p-adic

Subspace Theorem with unknowns taken from the ring of integers of a

number field

which was strong enough to imply the upper bounds mentioned in the

previous sections. We will not give the rather

complicated statement of this result.

By using a suitable specialization argument

from algebraic geometry

one may reduce

Theorem 1 to the case that

and the group

and the group  are

contained

in an algebraic number field,

and then subsequently one may reduce equation (2)

to a finite number of systems (9) by a similar argument as

above.

By applying the quantitative p-adic Subspace Theorem to each of these

systems

and adding together the upper bounds for the number

of subspaces for each system,

one obtains an explicit upper bound

for the number of subspaces containing the solutions of (2).

Considering the solutions

of (2) in one

of these subspaces, then by eliminating one of the variables one obtains

an equation of the shape (2) in

are

contained

in an algebraic number field,

and then subsequently one may reduce equation (2)

to a finite number of systems (9) by a similar argument as

above.

By applying the quantitative p-adic Subspace Theorem to each of these

systems

and adding together the upper bounds for the number

of subspaces for each system,

one obtains an explicit upper bound

for the number of subspaces containing the solutions of (2).

Considering the solutions

of (2) in one

of these subspaces, then by eliminating one of the variables one obtains

an equation of the shape (2) in  variables to which a

similar

argument can be applied. By repeating this, Theorem 1 follows.

variables to which a

similar

argument can be applied. By repeating this, Theorem 1 follows.

The proof of Schmidt's theorem on linear recurrence sequences has a

similar structure,

but there the argument is much more involved.

Next: Diophantine geometry

Up: Diophantine Equations and Diophantine

Previous: Linear recurrence sequences

(8)

(8)